We Can Do Hard Things -- Living Through a Pandemic and Other Lessons From History

Salt Lake Herald-Republican 1913-10-13

My Dad was born in 1912. His Dad was a government trapper in the mountains when he was born, and had arranged for his youngest sister Mamie to be with his wife during his absence. My Dad and his twin brother came early, he weighing a mere 1.5 lbs and his brother at 2 lbs. The birth was difficult and his mother died within the week. Aunt Mamie was left with the responsibility of trying to keep two tiny premature twins alive as well as care for three older siblings until my Grandpa came back from the mountains.

She placed the babies in a small blanket-lined box, kept warm with the glow of a single light bulb. Although my Dad Ed began to thrive under her care, his twin brother Ellis died at 3 months old.

When my Dad was 6 months old, his father remarried a widow who didn’t think she could take care of such a fragile baby, and so my Dad became Aunt Mamie’s baby.

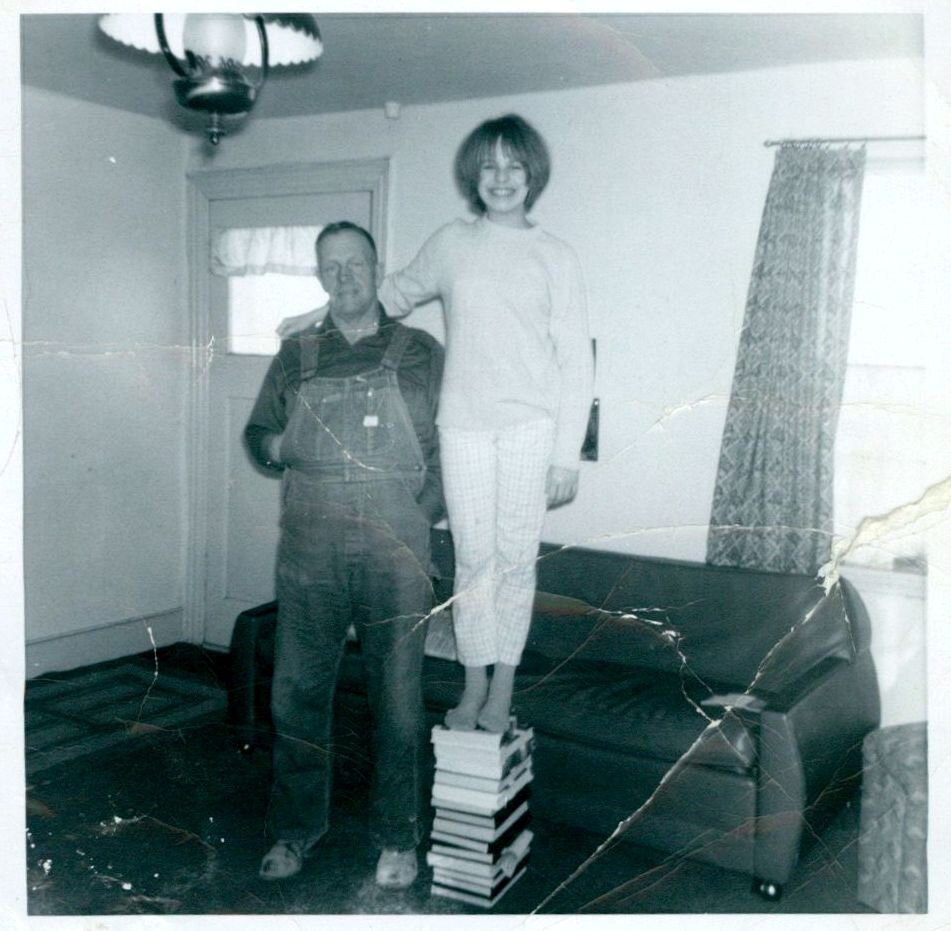

My Dad, the 24 oz. baby who thrived in a shoebox, the baby who was given away, grew up knowing that he could survive hard things.

He grew up in the days when horses were the main mode of travel — when water pumps and outhouses were in everyone’s back yards. A time when children read by candlelight, and worked alongside adults on crops and other jobs to maintain a simple life.

He was six years old during the 1918 Flu pandemic. My Grandson, who is named after my father, turns eight this week.

It’s easy to see the parallels between what happened to my Dad then, and what is happening to my Grandson today. In October of 1918, my Dad’s local newspaper, the Richfield Reaper, announced that because influenza was spreading through the county, the schools would be closed, as well as all public gatherings, and strict quarantines would be put in place to prevent the spread of the disease. The paper predicted that “it now looks as though it will be several weeks ere the disease will have run it’s course” (Richfield Reaper, Oct 19 1918, Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah).

In March, my grandson’s school announced a two week soft school closure. Many of his friends and neighbors anticipated that the school would be able to open again before the end of the year. In actuality, his school has been closed for the remainder of the year, just as, in November of 1918, the health department in my Dad’s town met and ordered that “all persons must wear masks in public, whether on the street or in business houses… This new attack has placed the lifting of quarantine more remote than ever and the hope of schools opening before the Christmas holidays is questionable” (Richfield Reaper, November 30, 1918, Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah). Today, just as then, things are closed down, we are wearing masks in public, and we are wondering how long this will last.

It took until February of 1919 until the schools in Richfield were finally opened, and even then, the paper reported, “Health authorities agree that the disease is less virulent as time passes, and as all other epidemics of this kind have recurred again and again for a period covering three years or more it is safe to count on the “flu” being with us for a long time. That being the case we cannot hope to maintain a quarantine during all that time” (Richfield Reaper, February 15, 1919, Digitized by J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah).

It remains to be seen what will happen to my grandson. How long will his school be closed and what will the world look like by the time it reopens? He hopes it will be soon. He keeps calling me to tell me about all the things we will do together “when this nonsense is over”.

Richfield Reaper. 1919-01-04

For my Dad, the Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was just the beginning of the “nonsense”. He grew up a poor kid in a rural town. He lived through World War I, the Great Depression, and World War 2. When he started raising a family, there was an ongoing polio epidemic, where tens of thousand of children were placed inside iron lungs with many thousands more quarantined at home. Polio was crippling 35,000 children a year. Parents were terrified to let their children go outside! Alongside of polio were other perilous diseases such as mumps, measles, and small pox. As a young father, my Dad watched as his children suffered from the diseases, praying for each child’s recovery and for vaccines to end the suffering.

His years of child-rearing were also filled with drills of “Duck and Cover” in the event of a nuclear attack, staples of the early 1960’s. Neighbors built bomb-shelters, food was stockpiled, and children were terrorized with under the desk drills, and the though of how the world would end with a nuclear attack. From the tumultuous 60’s came a decade of further fear and sacrifice.

With the ongoing Vietnam war, the 1970s began with a world falling apart. The economy was a mess, the stock market plummeted as it lost 50%. Lines for gasoline were formed as prices soared and was rationed for its scarcity. Airline flights were frequently hijacked, The United States President was impeached, student’s protested, and Vietnam became a winless war. This era was one of great unrest and uncertainty it was also the era of technological discoveries. The era that things began to develop at a quickening pace.

In the 1980s the American dream of owning a home was dashed as interested soared over 18%. The family farm that Ed had worked so hard to purchase was making very little money, and the interest on any farm loans made increase almost impossible. Yet Ed worked on — taking on a second job to pay the bills.

Through all of this, I watched my dad work hard with optimism, kindness for all, and with a genuine smile on his face. He was never discouraged by the difficulties he faced or the difficulty of the task, he just rolled up his sleeves and said, “This challenge only needs a bit of elbow grease!” I now know that his approach to life was formed by his growth mindset, of his knowledge that he could survive and thrive in the face of hard things.

My dad has been gone for two decades, and now my grandson’s childhood is beginning in a strikingly similar way—with a worldwide pandemic, but my Dad’s life and legacy live on, and he continues to teach our family and guide us with great example. From him I have learned I can do hard things. If I am asked to social distance —- to be away from my children and grandchildren — away from my students — I remember my dad Ed, the man who started life under a lightbulb in a shoebox and lived through decades of trials without ever loosing the light of hope and kindness. I’m hoping that when we come out on the other side of COVID-19, life’s challenges will have made me and my fellow humans a strong, kinder, and gentler people—just like my Dad.